Overview

Systemic Lupus Erythematsus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune diesease that occurs when the body's immune system attacks its own tissues. Inflammation caused by SLE can affect joints, skin, kidneys, blood cells, brain, heart and lungs.

FAQs

How can SLE present?

SLE can present in several ways depending on the type of autoantibodies present. Antibodies are typically produced by the immune system to protect us against infection but in the case of SLE and other autoimmune illness, the antibodies are autoantibodies and are directed against the patient’s own tissues. SLE symptoms can appear in patients in the form of rashes, arthritis, or low blood counts. SLE can also cause kidney inflammation that can lead to permanent kidney damage. Blood tests are very important in making a diagnosis of SLE, however many people without SLE can have a low-level or isolated positive antibody tests. It is important to speak with your care provider or rheumatologist if the ANA test (antinuclear antibody test) is abnormal as it alone does not prove SLE is present. Because of a high false positive rate, an ANA should only be checked when there is a high degree of suspicion for an autoimmune disease.

Who gets SLE?

9 out of 10 people with SLE are female, and SLE most often arises in women during the child bearing years, when estrogen production is highest. Grant Hughes, Associate Professor of Rheumatology at the University of Washington, has spent many years studying the role of hormones in causing SLE. Estrogen appears to increase a woman’s risk of developing SLE, but “Estrogen alone is not sufficient to cause lupus, otherwise most women would get lupus. You have to have a genetic risk and there are probably some other factors involved. Estrogen is just one of those factors.” In the U.S., SLE occurs more often in people of African, Asian, and Hispanic ancestry and less often in those of European ancestry. Of interest, men with a condition called Klinefelter’s syndrome are born with an additional female sex chromosome (XXY rather than usual male XY; women are XX) and are at a 14-fold increased risk of SLE over other males. Other risk factors for the development of SLE include genetic deficiencies in certain immune proteins.

What causes SLE?

Some fascinating work has been done over the last several years to understand why people get SLE. Everyone has immune cells that can react to our tissue as we develop in the womb. Many of these cells are recognized by the developing immune system and eliminated however a few survive into birth. These are controlled or suppressed by the immune system. For reasons that are being more and more understood, genetics and the environment work together to allow the cells that produce antibodies against our own tissue to lose that suppression and start producing self-directed antibodies.

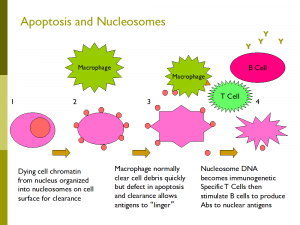

Dr. Keith Elkon, Professor and Director of the Division of Rheumatology, and his lab at the University of Washington are very involved in answering fundamental questions about SLE. The Elkon lab has been interested in the fact that people with SLE do not seem to clear the debris from our normally dying cells (apoptosis) very effectively. This delay can potentially allow the immune system to react to the DNA of the dying cells leading to the formation of the antinuclear antibodies that are important in the cause of SLE. They have also studied the important role of Type 1 interferon, an immune signal that helps us fight viral infections, but can also stimulate the development of SLE in susceptible people. Natalia Giltiay and Christian Lood in the Division of Rheumatology are studying how autoantibodies are formed and how they combine with dead and dying cells to drive inflammation in people with SLE.

What are the potential manifestation of SLE?

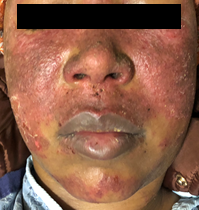

Skin: SLE patients can have a variety of rashes including discoid lupus that can cause skin scaring, the classic butterfly rash over the cheeks and nose known as acute cutaneous lupus, and a rash called sub-acute cutaneous lupus that appears in areas subjected to sun exposure. The rashes are treatable and all but discoid lupus are reversible leaving no scaring.

Skin: SLE patients can have a variety of rashes including discoid lupus that can cause skin scaring, the classic butterfly rash over the cheeks and nose known as acute cutaneous lupus, and a rash called sub-acute cutaneous lupus that appears in areas subjected to sun exposure. The rashes are treatable and all but discoid lupus are reversible leaving no scaring.

Hair: Hair loss is common in SLE but is rarely permanent. Hair usually regrows once the disease is controlled. Alopecia areata (pictured) is also common and results in a concentrated area of hair loss. This is also reversible with therapy. Extensive discoid lupus disease of the scalp can lead to permanent hair loss.

Hair: Hair loss is common in SLE but is rarely permanent. Hair usually regrows once the disease is controlled. Alopecia areata (pictured) is also common and results in a concentrated area of hair loss. This is also reversible with therapy. Extensive discoid lupus disease of the scalp can lead to permanent hair loss.

Joints: Stiffness, pain, and swelling can occur in multiple joints including the hands, wrists, elbows, shoulders, hips, knees, ankles, and feet. SLE does not affect the spine. It is an inflammatory form of arthritis and is usually worse in the morning and better with activity. Swelling may be mild to moderate. If chronic, the joints may drift to the side in what is known as Jaccoud’s arthropathy.

Joints: Stiffness, pain, and swelling can occur in multiple joints including the hands, wrists, elbows, shoulders, hips, knees, ankles, and feet. SLE does not affect the spine. It is an inflammatory form of arthritis and is usually worse in the morning and better with activity. Swelling may be mild to moderate. If chronic, the joints may drift to the side in what is known as Jaccoud’s arthropathy.

Lungs: Most commonly, the lining of the lung called the pleura can be inflamed. A person so affected may be short of breath and have chest pain with deep breathing. Sometimes, an SLE patient may present with inflammation of the small vessels in the lung. This can lead to what looks like a pneumonia or if more severe can cause more significant lung bleeding known as diffuse alveolar hemorrhage. This is a very serious manifestation and needs aggressive therapy. Other SLE patients can develop interstitial lung disease where inflammation in the lungs leads to scar formation and reduced lung tissue. Pulmonary hypertension is another manifestation of SLE where there is an increased pressure going from the right side of the heart to the lungs. All of the above will present with breathing difficulties. Breathing tests, CT scans, and ECHOcardiograms can be useful to evaluate people with SLE and breathing problems.

Heart: The most common heart manifestation in SLE is inflammation of the outside lining of the heart called the pericardium. People with this present with pain on deep breathing and with lying back. Rarely the heart muscle can be involved leading to heart failure and even rarer yet the heart valves can be affected leading to blood flow issues within the heart. An ECHOcardiogram is a useful tool to evaluate heart involvement in SLE.

Kidneys: Kidney disease or lupus nephritis is an important manifestation of SLE. An immune attack against the kidney can lead to acute kidney failure requiring aggressive suppression of the immune system to prevent permanent damage. This has been an area of active research and there are some very helpful medications to treat lupus nephritis. Monitoring the urine and a blood test for creatinine are critical, especially in people with certain types of antibodies directed against double stranded DNA.

Nervous System: SLE can affect the tissue on the brain leading to seizures, psychosis, movement disorders, and even mood disorders. Certain types of antibodies can be found in people with CNS lupus called anti-ribosomal P antibodies, anti-neuronal antibodies, and anti-phospholipid antibodies. Many of these CNS manifestations can be treated with immune suppression but may need also to use medications to treat seizures, or psychosis, or mood disorders. Dr. Elkon’s laboratory have studied the antibodies that occur in CNS lupus. Rarely the peripheral nerves can be affected leading to numbness and or weakness in the extremities. Even more rare is inflammation of the muscles in SLE. Muscle enzymes are typically elevated and weakness of the muscles in the shoulders and hips may be mild or severe. MRI scans of the brain, nerve/muscle studies, and blood tests may be used to evaluate nervous involvement in SLE.

Blood cells: It is common for the white blood cells, the red blood cells, and the platelets (important for blood clotting) to be low in people with SLE. The lymphocytes (immune cells) in particular can be low and are a clue to the diagnosis. Antibodies against these can cause their destruction and lead to infections, severe anemia, and problems with clotting if they reach extremely low levels. Treatment with immune suppressing medications can restore the levels to more normal range.

Other issues: Certain antibodies called the antiphospholipid antibodies can increase the risk of blood clots. These can form in or travel to critical areas such as the lung and cause problems with breathing and can be life threatening. Fatigue is also a common symptom in SLE and may be due to inflammation, medications, anxiety about the disease, lack of exercise, and poor sleep quality or some combination of these factors.

How is SLE diagnosed?

The combination of clinical symptoms and blood tests can make the diagnosis of SLE. As noted above, the ANA test has its weakness and needs to be used appropriately. The test should be done in two steps: first is the ANA test with a level or titer given such as 1:40 (patients serum diluted 40 times and the test is still positive) to 1:1280. Generally, the lower levels of 1:40 or 1:80 are not concerning. With the dilution factor or titer reaches 1:160 rheumatologists take notice. The second part of the test is looking for specific antibodies (called extractable nuclear antibodies or ENA) that give a character to the illness and predict manifestations. These include:

|

Autoantibody name |

Abbreviation |

Association |

|

Anti-Sjogren’s syndrome A |

SSA |

Found in SLE and Sjogrens syndrome. Associated with rashes and arthritis. Can also cause a rash, arthritis, and abnormalities in heart conduction in newborns if mother has this autoantibody |

|

Anti-Sjogrens’ syndrome B |

SSB |

Less common in SLE and more often in Sjogren’s syndrome |

|

Double stranded DNA |

DsDNA |

This autoantibody goes up and down with disease activity and can predict a flare if found to be elevated. Found in SLE patients with more severe disease such as CNS, kidney, or heart involvement. |

|

Anti-ribonuclear protein |

RNP |

People with this antibody can have Raynaud’s (hands turn white with cold exposure), arthritis, and lung fibrosis or pulmonary hypertension |

|

Anti-Smith |

SM |

Similar to RNP but also associated with kidney disease |

|

Anti-ribosomal P |

none |

As discussed can be seen in people with CNS disease |

|

Anti-phospholipid |

APLA |

Associated with blot clots; only about 40-50% of people with these antibodies will develop a clot |

|

Lupus anticoagulant |

LAC |

Similar to APLA |

An elevated ANA should be accompanied by one or more ENA to make a diagnosis of SLE. It is important to note that people can have a positive ANA and ENA antibodies with no discernable illness. These people should be followed by a rheumatologist to monitor the patient and intervene if necessary. It is also important to know that most people with SLE never need to be admitted to a hospital. Their illness can be managed in the clinic with regular check-ups, blood tests and prescribed medications.

How is SLE treated?

Medications are chosen depending on the manifestation and the intensity of the inflammation. The following are the most common medications used to treat SLE.

Prednisone: A quick acting and potent anti-inflammatory medication that can be used in low (5-20 mg), moderate (20-40 mg) or high doses (>40 mg) doses. Prednisone can be used for all manifestations of SLE and dosed according to the needs of the patient. Side effects include weight gain, infection risk, high blood pressure, difficulty sleeping, and increased blood sugar. Prednisone is often started along with more longer term medications as noted below then then gradually reduced to low level or off completely.

Hydroxychloroquine: Related to the naturally occurring anti-malarial compound, quinine, , hydroxychloroquine is an anchor drug in SLE. If is used for all types of manifestations in particular, arthritis and rash but has also been found useful to prevent kidney damage in lupus nephritis. It has a survival benefit in SLE and has been shown to reduce the risk of heart disease, diabetes, and cancer in SLE patients. Dosed 200-400 mg per day and currently is dosed on a per weight basis of 5-6 mg per kilogram. Side effects can include rash, loose stools, and after 10 years or more on the drug there is an increased risk of eye damage. Patients on hydroxychloroquine need yearly eye examinations after 5 years of taking this medication. Ok during pregnancy and may reduce the risk of certain problems in the newborn that can be caused by antibodies from the mother. Drs. Keith Elkon and Jie An in the Division of Rheumatology are using computer-aided drug design to develop new quinine-like drugs that might be safer and more effective for patients with SLE (link).

Mycophenolate: Used for more serious forms of SLE including CNS, kidney, and heart disease. Dosed 1000-3000 mg per day it has proven to be an excellent medication and is well tolerated. It is as effective as cyclophosphamide for kidney involvement with less side effects. Side effects do include stomach upset, low blood counts, elevated liver tests and risk of infection especially initially when prednisone is often used simultaneously. Cannot be use if someone is contemplating pregnancy as it can cause fetal damage. There is an alternative from of the medication called mycophenolic acid that is more expensive but easier on the stomach.

Cyclophosphamide: Used to be the gold standard for treating serious SLE and is still used. Given by mouth in pill form or can be given by vein every 2-4 weeks. It made a significant impact in the outcome of lupus nephritis for many patients before mycophenolate was available. Still a valuable medication for certain patients. Side effects can include low blood cell counts, serious infections, loss of ovarian function and early menopause, and bleeding from the bladder. Requires aggressive hydration after use if given by vein.

Belimumab: This a newer biologic agent that is given by vein monthly and can be used to treat SLE patients that have not completely responded to usual therapy. Suppresses B cells that make autoantibodies. Useful for multiple SLE manifestations. Side effects include infection.

Other medications: Azathioprine is an older medication that has been supplanted by mycophenolate but has the advantage of not crossing the placenta and thus safe in pregnancy. Used for SLE patients with more serious disease that would like to consider having a child. Methotrexate can be used in people with non-kidney manifestations such as arthritis or rash. Anti-inflammatories such as ibuprofen or naproxen can be used for mild manifestations such as joint pain or inflammation around the pericardium or pleura.

Other issues: Prednisone can have an effect on bone quality so getting adequate vitamin D and calcium in important. Making sure one gets sufficient sleep and gentle exercise is also important. Eating well to give the body the nutrients it needs is important. Also addressing risk factors for heart disease such as high cholesterol or high blood pressure is also very important. Finally, getting routine immunizations is an easy way to stay healthier.

How are we doing?

Compared to 20 years ago we are doing better! Medication management has improved, the use of mycophenolate has made a difference but still 20-40% of patients have less than an incomplete response to therapy so we still have room to improve. The future is bright though as we have learned and continue to learn more about SLE and new medications are on the horizon to treat this disease.

How can I help?

- The university of Washington has a repository of blood samples that allows us to do research. If you are a patient with SLE and want to participate please contact our Clinical Trials team at RheumResearch@medicine.washington.edu.

- If would like to donate to the research effort at the University which is very involved in finding a cure for SLE you can do so here.